In his essay “Dead Poets Society Is A Terrible Defense Of The Humanities,” Professor Kevin Dettmar argues that the film — by ignoring any in-depth critique of poetry in favor of enthusiastic, non-critical reading — does a huge disservice to the humanities and their history of intellectual rigor.

In his essay “Dead Poets Society Is A Terrible Defense Of The Humanities,” Professor Kevin Dettmar argues that the film — by ignoring any in-depth critique of poetry in favor of enthusiastic, non-critical reading — does a huge disservice to the humanities and their history of intellectual rigor.

If defending that history were the point of the film, I’d have to agree. But it isn’t. And what it is instead is far more valuable to our society, both now and when the film was released 25 years ago.

Dead Poets Society was the first movie that made me think about poetry. I was 16 when it came out in the summer between my sophomore and junior years of high school in upstate New York. DPS rolled over me like a huge wave, leaving me soaked in words (and tears) and feeling like I’d just been exposed to something new and dangerous and exciting. I was writing poems full of teen angst like many of my peers, but DPS connected those poems, and the longing and passion I tried to cram into them, to a legacy hundreds of years old.

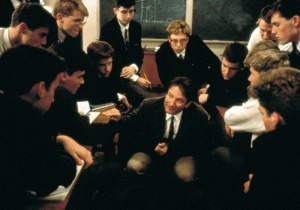

DPS was also the first film that sparked in me a desire to teach. And while that’s not the way I make my living, I’ve spent many hours in classrooms over the years as a guest lecturer on a variety of topics, and somewhere in the back of my brain is the image of Robin Williams huddled down in a cluster of expectant faces, imparting to those eager students the idea that they can be more than what they’ve been groomed to become. More importantly, that image is with me when I talk to my young sons.

Sure, Dead Poets Society gets some things wrong. That Frost line, most egregiously. But what it gets right is so important. Namely, the idea that words can ignite a fire in the human heart and mind. Mr. Keating, the character played by Williams, encourages his students to read poetry, to recite poetry, to listen to poetry, to write poetry. Dettmar points out that there isn’t much of the latter in the film, and he’s right. To that, though, I say two things.

First, where student verse is shown, such as when Charlie plays the saxophone and recites, that verse is also shown to capture the attention of the other students. Charlie’s saxophone-and-text piece, and his earlier piece written on the back of a centerfold, seem like jokes at first. But both pieces completely draw in his audience and end up showing that they, too, can create work that inspires.

Second, it’s incredibly important for people who want to write poetry to actually read poetry. In my own case, I wrote for years before I ever became a serious reader of poetry. When I did start reading, my writing immediately improved. Reading the work of others gave me so many more ideas. Other poetry showed what was possible, and hinted at even more possibilities to come. I devoured the books of poetry at Dove & Hudson Bookstore in Albany, NY, and found inside entire new worlds of language I’d never even considered. So if DPS is a little light on student writing, I say that’s OK. Let’s get people reading, too.

In a conversation tonight on Twitter, poet Caroline Shea wrote, “I don’t think you can have the critical thinking he calls for without the kind of enthusiasm DPS is founded on.” I couldn’t agree more. And if asked to choose, I’ll take enthusiasm every time.

Don’t get me wrong. I think a detailed critique of poetry, and a study of its methodology, is important. I could use more technical knowledge myself, and I know that my limited formal education means I miss things in poems that a more knowledgeable person would see. But even without that specialized training, I’ve been transported by a poem out of my world and into another. Poetry has also given me a deeper understanding of the life I’m living. Poetry is my superpower, my Spidey sense, the magic that lets me slow the world down and look at its constituent parts, or speed it up and imagine the curving road of the future.

I watched Dead Poets Society this week for the first time in two decades. I cried at the end, even more than I had when I first saw it. Why? Because it’s message is still clear, 25 years on: Language can change everything. It did for the boys in the film. It did for me.

My friend Noah Smith replied to this post on his own blog: http://utumbria.blogspot.com/2014/08/dead-poets-society-rebuttal-or-why.html

My response to his post is in a comment under the post.

[…] had on my identity (such as John Keating from Dead Poets Society, explained rather eloquently in this essay by my beautiful friend, Jason Crane), I’ll offer quotes that I have come across from friends and strangers that have touched me […]

You’ve hit the “sweet spot” my friend. It’s why I try to use poetry now to influence others, to see what can’t be seen, to know what can’t be known; it’s my sort of self-actualizing point in life, however feeble it might be. A real nice article, Jason. I’d like to post it on my Facebook page.