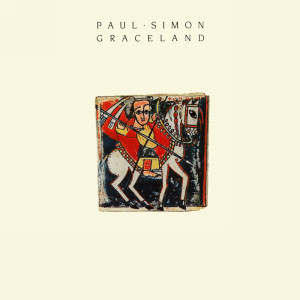

This afternoon I watched Under African Skies, a documentary about the making of Paul Simon’s album Graceland. In particular, the film deals with the cultural boycott against South Africa that existed at the time of the making of Graceland, and explores, via interviews with Simon and many others, the implications both then and now of his violation of the boycott.

I love Graceland. It’s one of my favorite albums, and I think it’s one of the greatest pop music albums ever made. It came out the summer before my freshman year of high school, and was a big hit with many of my friends. I also remember repeatedly watching a film of the tour. When I moved to Japan in 1991, one of the first things I bought was a collection of Simon’s music that included a CD of a live Graceland concert in Zimbabwe.

I love Graceland. It’s one of my favorite albums, and I think it’s one of the greatest pop music albums ever made. It came out the summer before my freshman year of high school, and was a big hit with many of my friends. I also remember repeatedly watching a film of the tour. When I moved to Japan in 1991, one of the first things I bought was a collection of Simon’s music that included a CD of a live Graceland concert in Zimbabwe.

I wrote a poem recently about Bishop Desmond Tutu and the anti-apartheid struggle, which was the first political fight of which I became aware in my life. As I wrote in the poem, my friends and I ordered anti-apartheid buttons from the Northern Sun catalog and wore them to school every day. The fight against apartheid was the very first step on the long path of my radicalization. However, at the time Graceland was released, it never even occurred to me that Simon had violated the boycott. To me, it seemed like a great way to expose more people to South African culture at a time when such exposure was sorely needed.

Many years later I became a professional organizer, and organized a boycott against an anti-union hotel. As anyone who’s ever taken part in a boycott knows, you take it personally every time someone crosses the line and violates the boycott. I was a paid organizer whose own livelihood wasn’t in any way harmed by the boycott. I can’t even imagine how much more intensely the South African organizers of the cultural boycott must have felt each instance of betrayal.

And yet.

And yet, I’m also an artist. I’m a poet and a musician, and music is by far the most sacred thing in my life. (I’ve written about that, too.) As I watched this film, I expected to side with the organizers of the boycott, but I found myself more and more siding with Simon, and even more with the South African musicians who recorded and toured with him. You know their names — Miriam Makeba, Hugh Masekela (my interview with Hugh), and Ladysmith Black Mambazo. To some degree, particularly in the case of Ladysmith, you know their names because they toured with Paul Simon, unless you were already a student of South African music.

Simon makes a compelling case for art, and for art’s need to resist being co-opted by governments of any kind. In the film, musicians such as Masekela (who was in exile at the time of Graceland) and guitarist Ray Phiri (who lived in South Africa) talked about being punished twice — once by apartheid, and then by a boycott that essentially prevented them from playing anywhere in the world.

Obviously it’s not my place to say whether Simon was right or wrong, and he doesn’t need either my absolution or my condemnation. I think history has largely proven that he made the right choice, or that at least his choice did a great service to global knowledge about the cultural vibrancy of South Africa. As for me, I think this film highlighted for me that my own tendency toward right-or-wrong activism was often too simple. There are more than two sides to most stories. And more ways to victory than are often imagined. And there’s a difference between a hotel boycott and a cultural boycott of an entire group of musicians. Still, if you cross my boycott or picket line, get ready to run. Meanwhile, let’s crank up the music.

Comments