This morning on my show I talked about the importance of direct action, and gave both local and national examples. We don’t need to wait for anyone to save us. We can do it ourselves.

Leave a CommentCategory: Politics & Activism

The new coat that doubles as a sleeping bag is all the rage on social media. Behind it lies the truth that we could feed and house everyone if we wanted to. We just don’t want to.

Leave a CommentGenerally speaking I don’t tell people how to protest, but buying Kellogg’s products is not protest. Here’s why.

Leave a Comment17 years ago, my friend David and I made a hip-hop track to support political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal. We called our band Buddha Mind. This, our only single, is “Freedom of Speech.”

Leave a Comment

This morning on The Morning Mixtape, I’m struggling to be upbeat in light of the hatred on display every day in our world. Here’s some audio from the show.

Leave a Comment I’ve been thinking recently about the types of activism I’ve been involved in over the past 25 years. For the most part I gravitate toward social and economic justice issues, and anti-war work. I’ve done very little, if any, environmental activism.

I’ve been thinking recently about the types of activism I’ve been involved in over the past 25 years. For the most part I gravitate toward social and economic justice issues, and anti-war work. I’ve done very little, if any, environmental activism.

Now, however, the more I look around at the world we’re living in, and the more I think about the planet on which my children will grow up and perhaps raise their own families, the more I’m convinced that there’s no greater need than to mitigate the effects of global warming.

I’m not talking about saving the planet. To quote one of my gurus, George Carlin: “The planet is fine. The people are fucked.” He was right. The planet will be here long after humans are gone. Nor am I trying to save the trees or the whales or the bottle-butted blue-nosed snorklewhammer. Instead, my desire to do more is motivated by two things, one selfish and one less so:

1. I’d like to have clean air to breathe and clean water to drink and healthy food to eat.

2. I believe in the principle of ahimsa, which means to do as little harm as possible.

Yes, I’d like there to be beautiful vistas and massive forests and rolling oceans and, you know, the Solomon Islands and all that. But really, it’s those two principles – self-preservation (and the protection of my children’s future) and the idea of doing as little harm as possible – that are motivating me.

Recently I’ve been reading Edward Abbey. I finished Desert Solitaire a couple weeks ago, and I’m reading The Monkey Wrench Gang now. It’s hard to read Abbey and not feel compelled to get out there and cause trouble in the name of stopping our continued destruction of our habitat. Plus I naturally tend toward direct action rather than lobbying or making phone calls. I believe in the words of Mario Savio:

“There’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part! You can’t even passively take part! And you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels … upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop! And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!”

I mentioned that I gravitate toward social justice and economic justice work. As it turns out, a benefit of working to change the way we live and the impact we have on our environment is that our most destructive behaviors tend to harm not only the environment, but also the people who do the work and the people impacted by that work.

At the root of all of this, in my opinion, is our unsustainable system of corporate capitalism and plutocracy. This means that working on environmental issues can very directly involve striking at the heart of our capitalist system. Two bulldozers with one stone, so to speak.

I’m not saying anything new, nor I have reached a definitive answer about the direction of my activism. But I do think it’s time for me to change what I’m doing, and start focusing on either stopping the destruction or, if it’s too late for that, on figuring out how to live in the very different world that will emerge. As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts.

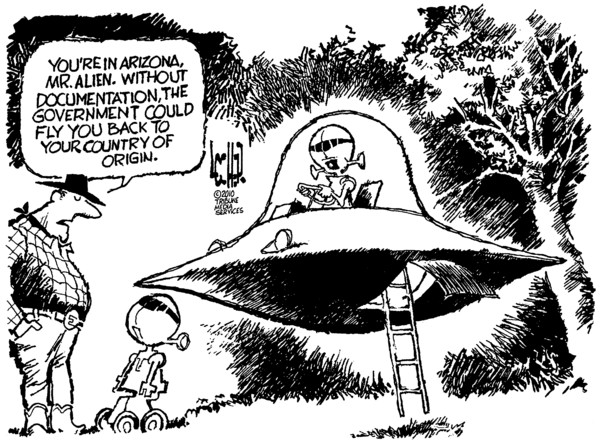

Leave a CommentThe Narrowness Of Our Thinking, or, A Message To Zort 137

As I, like you, surf the waves of this interminable election season, I am once again disappointed at the relative nearness of the horizon for which even the most progressive candidates are aiming. Yes, we have a socialist running for president, and yes, he seems to be doing fairly well (though nearly guaranteed to lose). But even the Great Septuagenarian Avenger can’t or won’t say what needs to be said about the system in which my children will grow to an increasingly despairing adulthood.

As a people, we have narrowed the scope of our thinking and limited the range of our compassion until any crumb dropped from the master’s table seems like manna from the heaven we mostly don’t believe in anymore. We’ve fallen so far that even the ideas of a patrician such as FDR seem like the radical ravings of a revolutionary compared with what we’ll now accept as progress.

Companies don’t send hundreds of thousands of jobs to distant lands (like Canada) because they otherwise stand to lose money. They offshore the work to make even more obscene profits than the merely profane profits they’d make if they kept those jobs here at home. The idea of ever-increasing profit is no longer even questioned. It’s taken as a given, like sunrises, death, and private health insurance. It’s been so long since the charter of any corporation was revoked – an act which, in these days of corporate personhood, is murder – that most citizens don’t even realize that’s an option. Corporations are here to stay, they must be profitable, and they may use any means necessary to achieve that end. The recent release of the Panama Papers is shocking only for the utter lack of surprise contained in those pages. We might have a few proper names that we previously lacked, but we certainly have no new information about the way our system works.

There is more than enough food to feed every person in the world. There is more than enough money to clothe and house and educate every person in the world. We have the technology and the resources to cure – or at least ameliorate the symptoms of – most illnesses. We know the kinds of food people should eat to remain healthy, and we know how to grow them with relatively little harm to the planet on which we live. These are not opinions. They are facts. That they seem like science fiction is only because we’ve lost the ability to think beyond … well, beyond. Here in The West, we’re raised to consume, taught to obey, and steered away from thoughts that might rock this leaky dinghy on which we’ve staked our meager survival. In the global south, the fight for survival is so clear and present that there aren’t extra hours in the day to imagine a world better than this, and even fewer hours with which to act upon such daydreams in any case.

Any sane observer of this planet – the aliens, say, that we have to hope won’t show up to marvel at our ineptitude – could only conclude that we are so hateful and lacking in compassion that we choose to let children starve while we build bigger weapons, bigger cars, bigger factory farms. Because otherwise how could the human race let this much suffering happen? The argument against the Biblical god is that He couldn’t possibly be all-knowing, all-powerful and all-loving, because babies die of malnutrition and innocent children are beaten to death. But using that same logic, it becomes harder and harder to believe in the existence of humanity. Perhaps we’ve been replaced, without our knowledge, by seven billion perfect copies with the hearts taken out.

In these debauched and dismaying times, it’s incumbent upon all of us to work to lessen the suffering of our fellow travelers on this spaceship. That’s an inescapable truth. But that lessening suffering is the apex of our hopes is the surest sign that this experiment – human life on earth – has failed. When the aliens do, inevitably, arrive, the best we can hope for is that we’re already gone. Zort 137 and its comrades can land, take a few selfies in front of moss-covered mounds that used to be skyscrapers, then head back onto the spaceways to meet up with other creatures who spent more time focusing on improving the lives of everyone than on poisoning and bludgeoning and short-changing and enslaving as many of their fellow beings as possible.

Zort 137, if you’re reading this, we’re not sorry. Most of us never really even realized we were doing it.

Leave a CommentThis afternoon I watched Under African Skies, a documentary about the making of Paul Simon’s album Graceland. In particular, the film deals with the cultural boycott against South Africa that existed at the time of the making of Graceland, and explores, via interviews with Simon and many others, the implications both then and now of his violation of the boycott.

I love Graceland. It’s one of my favorite albums, and I think it’s one of the greatest pop music albums ever made. It came out the summer before my freshman year of high school, and was a big hit with many of my friends. I also remember repeatedly watching a film of the tour. When I moved to Japan in 1991, one of the first things I bought was a collection of Simon’s music that included a CD of a live Graceland concert in Zimbabwe.

I love Graceland. It’s one of my favorite albums, and I think it’s one of the greatest pop music albums ever made. It came out the summer before my freshman year of high school, and was a big hit with many of my friends. I also remember repeatedly watching a film of the tour. When I moved to Japan in 1991, one of the first things I bought was a collection of Simon’s music that included a CD of a live Graceland concert in Zimbabwe.

I wrote a poem recently about Bishop Desmond Tutu and the anti-apartheid struggle, which was the first political fight of which I became aware in my life. As I wrote in the poem, my friends and I ordered anti-apartheid buttons from the Northern Sun catalog and wore them to school every day. The fight against apartheid was the very first step on the long path of my radicalization. However, at the time Graceland was released, it never even occurred to me that Simon had violated the boycott. To me, it seemed like a great way to expose more people to South African culture at a time when such exposure was sorely needed.

Many years later I became a professional organizer, and organized a boycott against an anti-union hotel. As anyone who’s ever taken part in a boycott knows, you take it personally every time someone crosses the line and violates the boycott. I was a paid organizer whose own livelihood wasn’t in any way harmed by the boycott. I can’t even imagine how much more intensely the South African organizers of the cultural boycott must have felt each instance of betrayal.

And yet.

And yet, I’m also an artist. I’m a poet and a musician, and music is by far the most sacred thing in my life. (I’ve written about that, too.) As I watched this film, I expected to side with the organizers of the boycott, but I found myself more and more siding with Simon, and even more with the South African musicians who recorded and toured with him. You know their names — Miriam Makeba, Hugh Masekela (my interview with Hugh), and Ladysmith Black Mambazo. To some degree, particularly in the case of Ladysmith, you know their names because they toured with Paul Simon, unless you were already a student of South African music.

Simon makes a compelling case for art, and for art’s need to resist being co-opted by governments of any kind. In the film, musicians such as Masekela (who was in exile at the time of Graceland) and guitarist Ray Phiri (who lived in South Africa) talked about being punished twice — once by apartheid, and then by a boycott that essentially prevented them from playing anywhere in the world.

Obviously it’s not my place to say whether Simon was right or wrong, and he doesn’t need either my absolution or my condemnation. I think history has largely proven that he made the right choice, or that at least his choice did a great service to global knowledge about the cultural vibrancy of South Africa. As for me, I think this film highlighted for me that my own tendency toward right-or-wrong activism was often too simple. There are more than two sides to most stories. And more ways to victory than are often imagined. And there’s a difference between a hotel boycott and a cultural boycott of an entire group of musicians. Still, if you cross my boycott or picket line, get ready to run. Meanwhile, let’s crank up the music.

Leave a Comment

I’m a big fan of comedian W. Kamau Bell. He and his wife and child had a harrowing-but-all-too-common experience at a cafe in Berkeley this week. He writes about it on his blog. Here’s the opening:

Leave a CommentDear Elmwood Cafe

2900 College Avenue, Berkeley, CA 94705You don’t know me. I know that for sure now. It’s not that I would expect you to know me, although many people in the Bay Area do, because of the work I’ve done as a stand-up comedian locally and on television. I’m known for something that The New Yorker called “intersectional progressivism.” That basically means I use jokes to fight for the people who don’t get a fair shake in the world. For the last several years, I have tried to learn as much as I can about oppression in all forms so that I can help make the world slightly more bearable with a few jokes. But that’s just my career.

In my life, I am a person who loves The Bay Area. LOVE IT! I lived in San Francisco for 13 years and in Oakland for two. And even though I lived in SF mostly, I spent A LOT of time in The East Bay. I have done my own headlining shows at The New Parish, La Pena, The East Bay JCC, and Marga Gomez’s comedy nights at The Marsh. I love these audiences. The Bay Area is a place where all sorts of different people live together, explore new ideas and strive to uphold the idea made famous by children singer Raffi, “The more we get together the happier we’ll be!”

To be honest though, my most fervent love is for Oakland. Which is why I was so excited recently when the people at Oaklandish gave me a hoodie. They just GAVE IT TO ME! I was walking past their pop-up shop at The Oakland Airport and one of their employees saw me, recognized me (I told you that people around here know me), and she awesomely and very generously gave me a hoodie. I love it. I wear it a lot. I was wearing it this past Monday, January 26, when I went to the Elmwood Cafe.

the memory hole (for Bishop Desmond Tutu)

Twice this week I talked to people

who didn’t know Bishop Desmond Tutu.

The small giant with the impish laugh

who strode across the landscape of my

high school years, my classmates & I

following behind with our END APARTHEID

buttons, ordered from the Northern Sun catalog,

pinned proudly to our rugby shirts. We grew up

in a county that was nearly 100% white.

Even now, more than two decades later, I

remember the name of every person of color

I met through the age of 18. We could have

all piled into a van if we’d wanted to go

to a protest together. But of course there

were no protests to go to in our town &

it hadn’t yet occurred to any of us to start one.

Still, we knew Mandela & we watched

Denzel Washington play Stephen Biko five years

before he would introduce us to Malcolm X.

It was safer for us to know about Tutu & Biko

& Mandela. They were thousands of miles

away in a bad place that mistreated black

people. Not like our town, where a young

black woman was the vice president of the

student council. See? We would have

spent the requisite class period on the

civil rights movement if we hadn’t run

out of time in the year & been forced

to end at World War II. Still, a few of us

had our buttons & we listened to Sting

sing about Chile & U2 sing about whatever

it was they were singing about & we felt

like the sun would always shine on us.

On some weekends we’d go to the lake,

stand on the end of the pier & look out at

Squaw Island, where women & children

fled as Sullivan’s soldiers flowed like a

rushing river over the land, trying to

extinguish the flame of the Iroquois.

It turns out that story might not be true;

that in fact the island is more likely

to have been a staging area for the

Iroquois resistance. I can’t imagine why

no one taught us about that. But I digress.

This is not a poem about America.

This is a poem about a man of the cloth

in a faraway land where people

were once judged on the color of their skin,

not the content of their character.

This is not a poem about America.

This is a poem about a country where

black people had fewer rights & fewer

opportunities than white people.

This is not a poem about America.

This is a poem about a religious leader

who said enough is enough & that his people

must stand up against oppression.

This is not a poem about America.

This is a poem about a place so evil

that white men with guns could shoot

black men without guns with no fear of

reprisal or consequence.

This is not a poem about America.

This is not a poem about America.

This is not a poem about America.

/ / /

Jason Crane

25 January 2015

Oak Street

I cannot threaten death

(Original Text: “Beyond Vietnam”

by Martin Luther King, Jr.

4 April 1967)

this magnificent conscience

leaves us in full accord

these words call us in time of war

of dreadful conflict

we must move

the silence of the night is limited

but the darkness seems so close

I called for the heart of the King

Aren’t you hurting?

I trust

I believe

I come not to the ambiguity

nor to the resolution

they are never resolved

I wish to speak

I am shining as if

I would never see an enemy

eight thousands liberties die

in brutal silent cruel manipulation

awareness would change our nation

the violence in the boys

we chose

O America America America!

now America destroys

I cannot threaten death

God is helpless and outcast

bound by human hands

madness within the people

hear their broken cries

we refused them

poisoned the land

we were reckless, tragic

the peasants watched

as we read promises of peace

where they know our bombs

they watch their children beg

our tortures are

their most cherished bitterness

to speak of liberation as aggression

is the right question

we are bombs, armies

we do not negotiate

they moved the truth

claimed that bombing, shelling, aggression

are the process of the sophisticated

stop

stop

I calculate the image of violence

stop

I begin

we must make

we must provide

we must continue

we must be

we must protest

the struggle is a reality

and a dozen other names calling God

we have seen helicopters napalm

the peaceful

incapable of justice

the Good Samaritan beaten and robbed

capitalists with no concern

burning human veins

year after year

America

the United States of poverty

insecurity and injustice

shirtless and barefoot in darkness

our only hope

in the final analysis

is in the ultimate reality of love

we can afford the oceans

we are fierce, naked, adamant

we must move

let us tell of hope

of solidarity, of history

as every nation comes in truth

each goes by truth and behind the shadow

we will make our world beautiful

/ / /

Jason Crane

2010

NOTE: You can hear this poem and see it in context here.

Leave a Comment